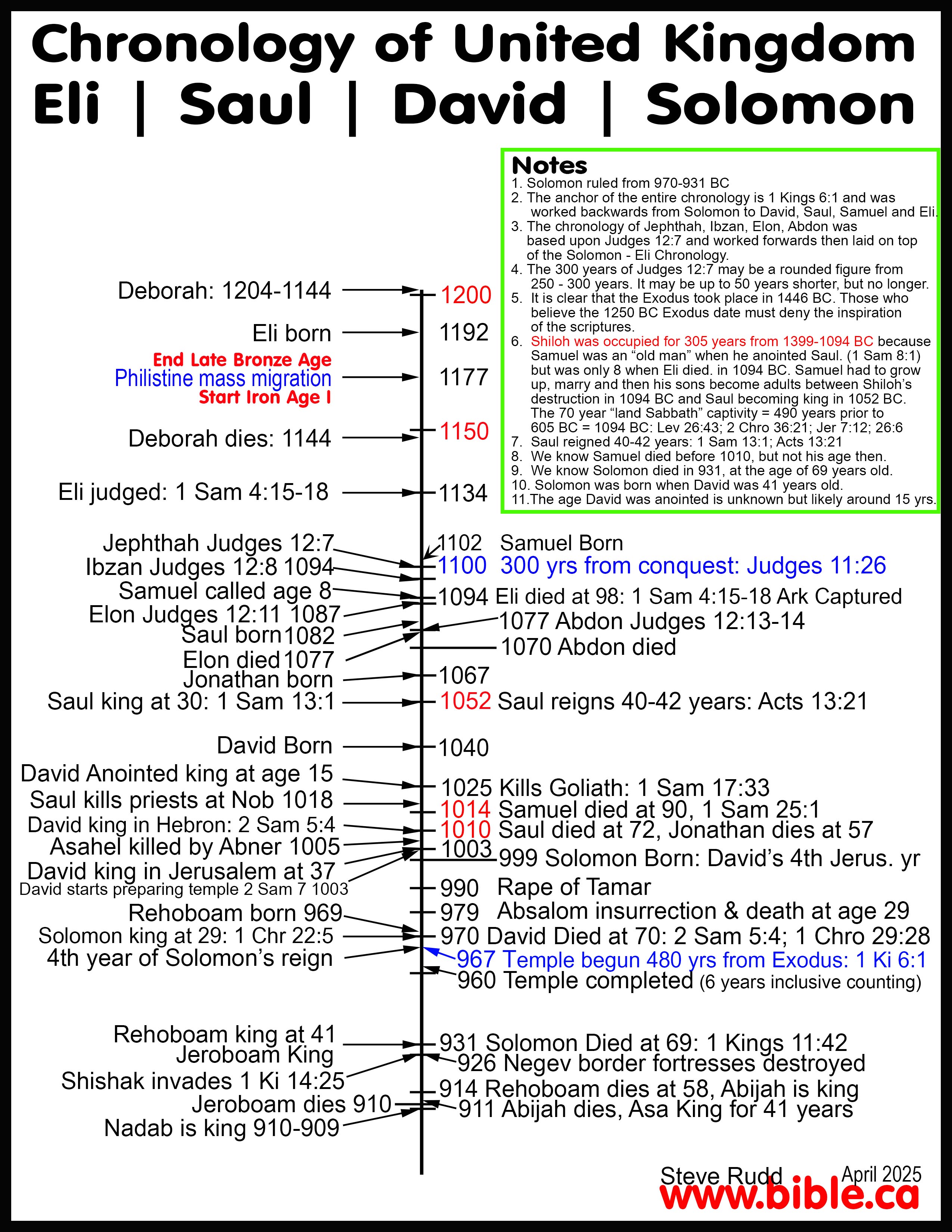

The date of the Biblical Exodus-Conquest is clear. 1 Kgs and 1 Chr –37 converge on a date of BC for the exodus and the Jubilees.

Table of contents

- Recent Research on the Date and Setting of the Exodus

- Navigation menu

- The Date and Pharaoh of the Exodus?

- Recent Research on the Date and Setting of the Exodus

However, the late-date Exodus allows only years for Joshua and the Judges, while the early-date Exodus, allows years. There are several benefits to the earlier date.

Recent Research on the Date and Setting of the Exodus

Some scholars spiritualize this to mean 12 tribes x 40 years of trials. This lets them use the BC date. In , Jephthah states that the Israelites had possession of the land for some years. Naturally, this scenario is untenable as Jephthah lived long before Solomon or Saul, for that matter was born. With a late-date Exodus, Joshua would have had less than 20 years to establish the nation of Israel in time for Merneptah to destroy it. This also involved careful study of the process of producing those documents from the oral traditions of a culture and from the compilations of previous documents, as well as the role of the compilers and editors, and the influence those factors had on the reliability of those sources and documents for reconstructing history.

This concern with sources built on the understanding that ancient documents were not just the recording of data, but were also the interpretation of history from the perspectives of a later community that saw the past not in terms of facts but in terms of meaning and ongoing significance for that community.

Navigation menu

By the end of the 19th century, this led historical investigation of the Bible to focus on the source documents and traditions that lay behind the written text, the social and cultural communities that produced the texts, and the complexity and diversity of the Bible. This simply meant that historical questions could no longer be answered by simply quoting a passage from Scripture. Also, a great deal of extra-biblical historical information in the form of ancient documents and inscriptions, as well as a whole range of artifacts and other physical remains of ancient civilizations began to be available during the 19th century as archaeology emerged as a tool of historical investigation.

For the first time, there was available a great deal of information that could be used by historians to verify and crosscheck the biblical accounts. While historical evidence cannot "prove" most of the biblical material, simply because it is largely theological in nature and cannot be proven empirically, it can provide the kind of objective verification for which historians seek. The results in many cases were mixed.

That is, in some cases the new historical evidence tended to support in a general sense the biblical accounts when those accounts touched on historical matters. For example, there had been considerable doubt from some historians during the 19th century about the existence of a people called the Hittites simply because they had no evidence about them. Yet in the early 20th century, the ancient empire of the Hittites was discovered in central Turkey revealing a well-established civilization in the late second millennium BC. However, in other cases the biblical accounts simply could not be reconciled with the historical evidence that came to light, as we shall see later concerning the exodus.

Some still contend that the Bible is absolutely inerrant in all matters, and therefore must be absolutely accurate in all aspects of historical accounts see The Modern Inerrancy Debate.

The Date and Pharaoh of the Exodus?

They argue that if we could just find more evidence we would be able to prove the biblical accounts. Others conclude that the Bible is simply not always a totally reliable account of "what really happened" from the perspective of modern historical criteria since that was never its intent. There is also consideration of differing worldviews, of different cultural perspectives, and of different ways of describing the world that may not correspond to our modern assumptions and categories.

It is this difference in perspectives that continues to mark the two opposing poles in several historical questions in Scripture, including the date of the exodus. What has emerged from these sometimes conflicting perspectives applied to the historical question of dating the exodus are two dates for the exodus that really represent more periods of time than exact dates.

Recent Research on the Date and Setting of the Exodus

The early date is usually placed in the middle 15th century around BC, while the late date is usually assigned to the close of the 13th century around BC. The early date relies most heavily on two specific biblical passages understood literally, while the late date relies on a more general view of the nature of Scripture combined with archaeological evidence. Both views depend heavily on assumptions concerning both the nature of Scripture and the methods of study used, as well as rational deduction based on those assumptions.

It is for this reason that a brief survey of the debate may help illustrate how such opposing views can arise from conflicting assumptions and methods of historical research. For many, the primary evidence in establishing a date for the exodus, or for any historical question relating to the biblical accounts, is simply the Bible itself. While certainly recognizing the need to be faithful to the biblical text, this approach is not as simple as it might sound, and raises a series of questions and difficulties in how it is actually practiced.

Does the Bible intend primarily to communicate to us the data of history? Can we automatically assume that the Bible directly answers the kind of historical questions that we want to ask of the biblical text? This moves to questions about the nature of Scripture. The very fact that many historical questions relating to the Bible have been debated for centuries suggests that there are not definitive answers to the historical questions in Scripture.

That is, the historical evidence to answer the kinds of questions that we pose to Scripture is often very meager. Is it possible that this is because the Bible was never intending to answer those questions? Is the Bible really intended to be a book of data from which to reconstruct precise history, or is its primary purpose something different? If we are going to use the Bible to answer historical data questions, then how are we going to deal with the great number of instances in which the biblical perspectives do not agree?

While it serves no real purpose simply to list discrepancies as if that somehow discounts what the Bible says or teaches, when we ask historical questions those discrepancies force themselves to the foreground. We are often then left with making decisions about the Bible as a source of historical evidence. Some choose to assume that the Bible is always correct in everything it says, and so approach historical investigation from the perspective of trying to prove that even conflicting perspectives are both correct in some way, or even that there are no real discrepancies at all.

- The Exodus.

- The Early Date.

- Main Navigation.

But this raises problems for historians who want to follow evidence and interpret that evidence, not be forced to fit the evidence to a preconceived idea about what the evidence ought to say. These and other questions suggest that trying to use the Bible to answer historical questions, or even of using historical evidence to "prove" the validity of the Bible is a very complicated task that goes far beyond simply assuming that the Bible tells us everything we want to know about history.

The fact is, the Bible has very little that can be used to address the historical question of the date of the exodus, which leads to differing opinions. If we assume that the number is to be taken as a precise number of years much as we would count years on a calendar today, working backward from this date we arrive at a date around BC for the exodus. This is the primary origin of the BC date for the exodus. While we might expect that the number here is precise and intended to tell us exactly how many years, that is largely an assumption from our modern perspective of data-based thinking and history writing.

But we have no indication that the ancient Israelites viewed timekeeping in the same way that we do in a modern scientific age. In fact, both our own history and even modern experience of tribal cultures tells us that scientific approaches to history keeping are a relatively modern invention. Also, this assumption does not consider the fact that numbers were used for other purposes in ancient Israel than just precise counting.

A great many numbers in both Testaments are used symbolically, are stylized for other purposes than simple counting, or are approximate numbers based on different cultural ways of reckoning time than just counting years.

There are several groups of numbers that specifically function in such roles, for example the number three often used simply to mark the passage of a short period of time or extent without intending specifics; Jon 3: Some of these numbers are then used in multiples for much the same purposes, such as 70 or 77 10 x 7, or double 7s; note Gen 4: This has led many scholars to conclude that the number in 1 Kings 6: This suggests that the numbers used are not accidental or random since the number symbolizing community 12 is combined with a number used to signify a generation That is, the verse says that between the exodus and the construction of the Temple there were approximately twelve generations, enough time for the community that needed the temple to emerge.

That is not a specific period of time but an approximation based on how ancient Israelites tended to mark the passing of time, that is, according to generations of people. To attempt to translate that into specific years is a precarious undertaking since we can only guess based on modern analogy.

But if we use the approximate period of 25 years for a generation between a father and a son, then we end up with about "clock time" years. Working backward from BC, this suggests a date of around for the exodus. But this is probably too speculative to be of any real use, since this tries to translate numbers that are used for one purpose into the service of questions that force them to be used for another purpose. This occurs in a message from Jephthah the Judge to the king of the Ammonites trying to persuade him to stop campaigns against the Israelites in the Tranjordan territory.

The king of Ammon was attempting to retake some of the Ammonite territory that had been lost to Israel in the time of Moses. The time period of the Judges is notoriously difficult to define, simply because there are few details that can be cross-referenced for precise dating. If we follow the generally accepted chronology of John Bright, the period of the Judges was between and BC. If we allow for the activity of the other Judges, we can roughly place the time period of Jephthah around BC. By adding another 40 years for the wilderness wandering, this leaves a date approximately BC for the exodus.

This conclusion is based on several broad assumptions about the text that renders it less than useful as evidence for any date. Second, even in the context of the narrative, Jephthah is not portrayed as one who would necessarily have any information as to the exact extent of time. He would have had no access to historical records in order to speak with precision. It could be argued that we are not really listening to Jephthah here but the narrator who would have had access to that information.

But again, if that is the case and the narrator wanted the dates to be significant and precise, then it seems logical to assume that other details of the narrative that relate to dating would be more evident. In either case, whether the narrator or Jephthah, it does not appear that precision in dating is a concern of the narrative. Finally, the lack of precision of dates in the entire period of the Judges hampers trying to construct a logical deduction such as this. Even the dates posited by historians are only general time frames based on meager evidence.

That suggests that any such logical deduction about exact dates is already compromised by the lack of adequate chronology and datable historical records for the period. A second kind of argument for a 15th century date appeals primarily to archaeological evidence, since there are virtually no historical documents from this era that can be used as evidence to confirm or challenge the biblical account.

The archaeological evidence primarily consists of excavations in those cities that are mentioned in the biblical accounts as captured and destroyed by the invading Israelites. There is no archaeological evidence of the exodus itself, so we are left with making deductions based on the evidence from the later presence of Israel in Canaan.